The Arab American News

RAMADAN 2011

18

I

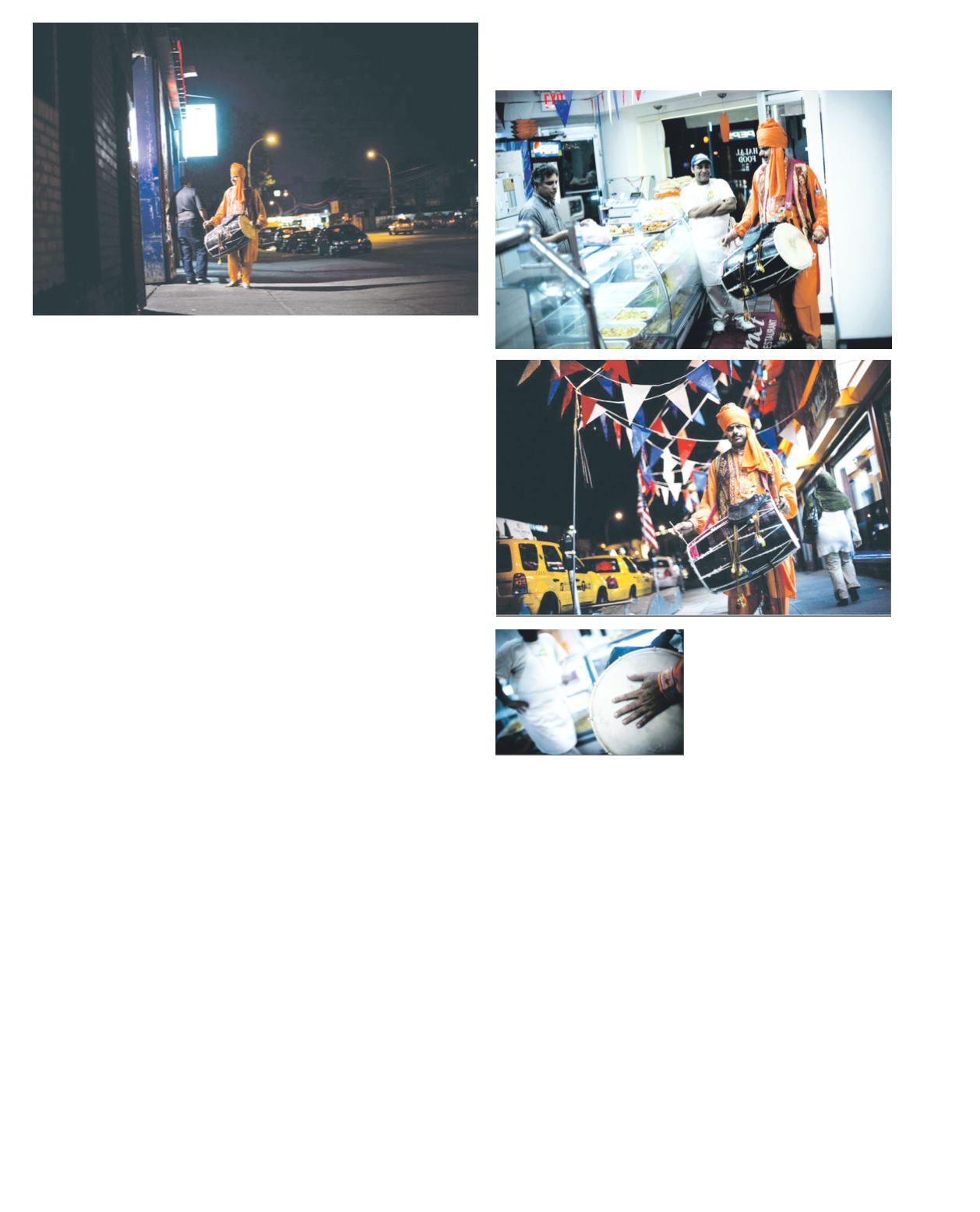

t was just past four the other morn-

ing when Mohammad Boota pulled

his Lincoln Town Car into a service

sta on on an industrial stretch in Long

Island City, Queens, and bounded out

— a typhoon of embroidered fabric,

good cheer and unusual urgency.

“I’m late today,” he explained as he

popped the car trunk, hauled out a bar-

rel drum, grabbed two rough-hewn

wooden s cks and, as a few bewildered

mechanics watched, pounded out a

galloping rhythm. The clamor echoed

off a nearby hotel.

Boota, a limousine driver, has built a

sideline as a ceremonial drummer for

his fellow Pakistani immigrants. He is

also New York City’s foremost — and

perhaps only — Ramadan drummer. A

few hours before dawn during the holy

month of Ramadan, drummers

throughout the Muslim world take to

the streets to wake the faithful in me

for a meal before the day me fast.

Boota, 54, introduced the ritual to

the darkened streets of Brooklyn

about eight years ago. But a er his

drumming roused a spate of noise

complaints, he restricted himself to a

few blocks along Coney Island Avenue,

where many Muslims live. This year,

however, he has decided to push back

— gently. Ramadan began on Aug. 11

and ends on Thursday, and on this re-

cent morning Mr. Boota was taking the

tradi on farther afield, pioneering

new drumming territory in Queens.

His plan was cau ous. He intended

to play only in front of Pakistani-owned

businesses — gas sta ons, corner

stores, restaurants — and never as

loudly as he might were he in, say, Is-

lamabad or Karachi.

“I’m not going to play where people

have a problem,” he said, wearing a

shimmering orange shalwar kameez —

a tradi onal two-piece ou it — and a

matching turban. “We, the Muslim

people, already have so many issues.”

“I want people happy, dancing, eat-

ing,” he added. “I want to keep every-

body happy.”

He was responding to demand, he

explained. Since The New York Times

published an ar cle about him last year,

Pakistanis and other Muslims have

asked him to come play on their blocks.

“They say, ‘Why don’t you come to

our place, too?’ ” said Boota, who im-

migrated in 1992 and lives with his wife

and eight children in Coney Island.

“They want me. Everybody happy!”

But now me was of the essence:

Only about half an hour remained be-

fore everyone would already be up and

heading to morning prayer. In the his-

tory of Ramadan, countless drummers

have been stayed from their rounds by

war, flood and pes lence, but probably

none by early-morning e-ups on the

Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

As Boota hammered at his drum in

the service sta on, a Pakistani me-

chanic whooped, pulled out a cell-

phone and began dancing a jerky,

head-wobbling two-step, holding his

phone alo , relaying the performance

to a friend at the other end of the line.

Less than a minute later, however,

Boota abruptly stopped. “Ready to

go?” he asked, before jumping into his

car.

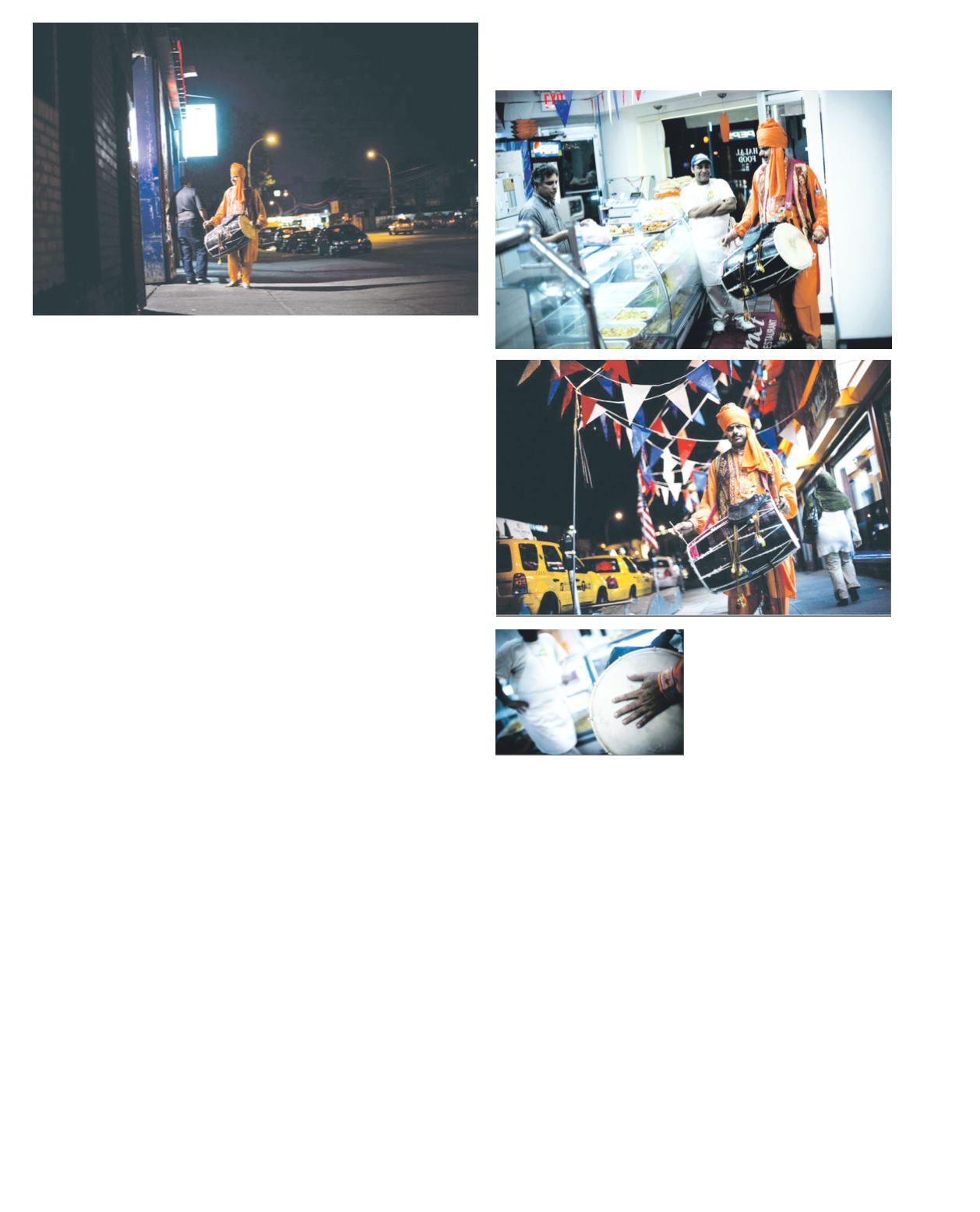

Several blocks north, he pulled into

another service sta on, Punjab Auto

Repair, also Pakistani-owned. Same

drill.

As he plastered the walls of the me-

chanic’s bay with percussive sound,

Imran, the manager, said Boota was

maintaining an important custom, even

if its usefulness had been eclipsed long

ago by the alarm clock.

“It’s Pakistani culture,” said Imran,

who gave only his first name. Then he

nodded at Boota. “He’s a very famous

guy,” he said, proudly.

Suddenly, Boota was back in his car.

“Thank you, mister,” he called out the

window to a mechanic. “God bless you,

Monday-to-Friday guy!” And in short

order, he had driven several more

blocks north, played inside a nearly

empty Pakistani restaurant in Astoria,

and was barreling southeast on the

B.Q.E. toward Jackson Heights.

Even though the debate over a

planned Islamic center near Ground

Zero has made some Muslims in New

York fearful of calling a en on to

themselves, Boota never considered

suspending his street drumming.

“This is America — America has a

Cons tu on, freedom of religion,” he

said. “We’re not doing anything

wrong.” He blamed poli cians for in-

flaming the issue. “The poli cal people

are just trying to make the big smoke,”

he said.

Arriving in Jackson Heights, he

parked on Broadway, where two large

Pakistani restaurants face each other

from opposite sides of the street. Ex-

cept for twomen drinking coffee on the

sidewalk, the block was empty. Boota

sha ered the quiet.

“What is this?” one man asked. “Is

this somebody’s birthday?”

Several others came to the windows

of Gourmet Sweets and Restaurant. The

owner teased himabout arriving so late.

“Time is gone,” Boota sighed, step-

ping inside the restaurant and playing

briefly.

“It’s like my big family,” he said, then

sat down for a cup of tea.

This ar cle was originally published in

The New York Times, September 5,

2010.

A Ramadan drumbeat

is sounded in Queens

“I want people

happy, dancing,

eating. I want to

keep everybody

happy.”